- Original Article

- Open access

- Published:

Three dimensions of the relationship between gender role attitudes and fertility intentions

Genus volume 77, Article number: 15 (2021)

Abstract

The relationship between gender role attitudes and fertility intentions is highly debated among social scientists. We emphasize the need for a multidimensional theoretical and empirical approach to extend the two-step behavioral gender revolution approach to a three-step attitudinal gender revolution approach distinguishing between gender roles in the public sphere, mothers’ role in the family, and fathers’ role in the family. Using the Generations and Gender Survey of eight European countries, we demonstrate the usefulness of such an approach. Gender equal attitudes related to the public sphere are more widespread than those concerning mothers’ or fathers’ roles in the family. Our results show that the association between gender role attitudes and fertility intentions varies—in terms of significance and magnitude—according to the dimension considered (gender roles in the public sphere, mothers’ and fathers’ role in the family), gender, parity, and country. We conclude that without a clear concept of and empirical distinction between the various elements of the gender role attitudes/fertility nexus, scientific investigations will continue to send conflicting messages.

Introduction

One of the most fundamental social changes in industrialized countries since the middle of the twentieth century has been the shift toward greater gender equality in attitudes concerning women’s and men’s roles in both society and the family. The focus has mainly been on women (e.g., Brewster & Padavic, 2000; Inglehart & Norris, 2003; Jansen & Liefbroer, 2006; Lesthaeghe, 1995; Scott, 2008; Testa, 2007; Thornton & Young-DeMarco, 2001; van Egmond et al., 2010). Gender equal attitudes have not spread equally across all social groups and developed Western societies. In general, women hold more egalitarian attitudes than do men (Brewster & Padavic, 2000; Ciabattari, 2001; Davis & Robinson, 1991; Kane & Sanchez, 1994; Scott, 2008), and across Europe and the USA, countries vary greatly in the extent to which gender equality has become socially accepted (Inglehart & Norris, 2003).

In family demographic research, gender and gender equality have become important features in understanding low fertility. However, the way in which gender equality relates to fertility is contested, and empirical findings vary depending on which indicator is used, whether women or men are studied, and which parity is considered (Neyer et al., 2013). People’s views of women’s and men’s roles in society and the family are part of this puzzle. The aim of this article is to investigate the relationship between gender role attitudes and fertility intentions.

Gender role attitudes Footnote 1 are different from gender behavior, but they are important for understanding intentions and actual behaviors (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1973). Gender role attitudes reflect what a person or a society in general conceives to be the appropriate, expected, and preferred behavior, while gender behavior is what people actually do. People have different expectations about how women and men should behave in both society and the family, which are assumed to influence their desire for children. However, empirical findings on the relationship between gender role attitudes and fertility are ambiguous (Goldscheider et al., 2010; Kaufman, 2000; Miettinen et al., 2011;Philipov, 2008 ; Puur et al., 2008 ; Westoff & Higgins, 2009).

Using data from the USA and focusing on gender roles in the family, Kaufman (2000) finds that men with egalitarian attitudes are more likely to intend to have a child, while the opposite is the case among women. Using the same data, Torr and Short (2004) find no significant relationship between egalitarian gender ideology and the likelihood of a second birth. In Europe, several studies using the same data come to different conclusions (Philipov, 2008; Puur et al., 2008; Westoff & Higgins, 2009). Focusing on women’s gender roles in 10 European countries, Philipov (2008) finds no link between gender attitudes and intentions to have a subsequent child. First-birth intentions and gender role attitudes correlate in some countries, but not in others. In addition, women with egalitarian attitudes have less intention to become parents, while the reverse holds for men (Philipov, 2008). Focusing on men’s gender roles, Puur et al. (2008) find a positive relationship between men’s egalitarian attitudes and fertility aspirations, while Westoff and Higgins (2009) focus on more general gender roles and find a negative relationship. Combining a wide range of items on the gender role expectations of women and men into one measure, Miettinen et al. (2011) find a U-shaped relationship between gender role attitudes and fertility intentions among men in Finland. Both the most egalitarian and the most traditional men appear to be most eager to become fathers, while the impact of gender attitudes is smaller and more ambiguous among women.

At first sight, the lack of uniform findings on the relationship between individual gender role attitudes and fertility is puzzling. Demographers mainly assume that gender equality boosts fertility (McDonald, 2000); thus, they also assume that gender egalitarian attitudes stimulate fertility intentions. Yet, the literature clearly indicates that empirical differences in prior findings may be related to the use of different measures of gender ideology (Arpino et al., 2015; Goldscheider et al., 2010; Miettinen et al., 2011). We argue that a concept of gender role attitudes that follows only the dimension of traditional versus egalitarian is insufficient to capture the links between gender attitudes and fertility intentions. Gender role attitudes may concern roles in the family or public sphere, target women’s or men’s roles, and vary across countries.

We give three reasons why these distinctions are necessary. First, gender is a structuring element of all relationships in societies (Scott, 1986). As such, gender roles are found in different areas of life. Therefore, we need to distinguish between the expected positions of women and men in the public sphere and those in the family. Second, the relationship between gender role attitudes and fertility intentions may differ between women and men because gender equality influences their lives differently. Most studies on the relationship between gender equality and fertility focus on women. The omission of men may give a distorted picture of the association between gender equality and fertility (Watkins 1993). We need to acknowledge this and investigate the relationship between gender-role attitudes and fertility intentions for both women and men. Third, this relationship may vary across countries. Countries vary regarding the prevalence of traditional or egalitarian attitudes toward women’s and men’s roles in the public and private spheres (Sjöberg, 2010), but also by factual gender equality (Evertsson, 2014) as well as the extent of support for gender equality by the welfare state. A cross-national perspective is needed to gain a better understanding of the association between gender role attitudes and fertility intentions and to examine the linkage across countries.

As demographic research puts greater emphasis on investigating the relationship between gender equality and fertility, a theoretical framework is required that takes these different dimensions of gender ideology into account. This implies a need to distinguish between gender role attitudes related to the public and private spheres and to women’s and men’s gender roles, and to account for country differences in these gender role attitudes.

Theoretical framework to link gender role attitudes and fertility

Throughout modern societies, there has been a long-term trend toward greater gender equality. However, the move from gender-segregated roles for women and men to more gender-equal roles has not been uniform (England, 2010), but rather, a gender revolution in two steps (Goldscheider et al., 2015). That is, the movement toward gender equality starts with women taking part in politics, employment, and education, followed by men becoming more involved in family matters (Goldscheider et al., 2015). The two-step gender revolution therefore targets women and men in different ways. The first step mainly concerns women and their participation outside the home, and the second mainly concerns men and their participation in family work. Researchers in general agree that the first step lowers fertility because employment and/or public engagement put a “double burden” on women if there is no concomitant change in men’s family behavior (Goldscheider et al., 2015; McDonald, 2000).

The second step of the gender revolution, namely men’s participation in household work and care, is expected to lead to a more gender-symmetric arrangement of family responsibilities; researchers argue that this supports fertility decisions (Goldscheider et al., 2010; McDonald, 2000). Although most industrialized countries follow this two-step movement toward gender equality, there are large variations in the process between them. The Nordic countries are often described as forerunners in the process of gaining gender equality. The countries of Southern Europe lag behind in women’s integration into the public sphere, as well as in men’s participation in family work. The continental Western European countries lie between these two country groups, with the German-speaking countries being more gender-conservative and France more gender egalitarian. With their focus on the full employment of both women and men, the former communist Eastern European countries had once been far ahead of the West in accomplishing the first step of the gender revolution; however, gender equality in the family had hardly been an issue. Since the fall of communism, these countries have experienced a backlash in terms of women’s participation in the public sphere (Funk & Müller, 1993; Gal and Kligman 2000a, 2000b; Szelewa & Polakowski, 2008; Saxenberg, 2014), no substantial changes have been made toward greater gender equality in the private sphere. Despite some progress, no countries—not even the Nordics—have achieved complete gender equality in either sphere, and many countries have not entered the second stage of the gender revolution to an extent that would herald changes in men’s roles in the family.

The long-term consequences of the shift toward greater gender equality are difficult to anticipate (Oláh et al., 2021). On the one hand, Sullivan et al. (2014) conclude that institutions and social norms will progressively adapt to the changing roles of men and women, so that work–family conflicts will no longer inhibit fertility in the long term. On the other hand, Okun and Raz-Yurovich (2019) suggest that as men contribute more to the domestic sphere, couples’ fertility may not increase to the extent predicted by gender theories of family change. After all, as men take on more domestic responsibilities, they may, like women, experience role incompatibility and therefore be less willing to agree on at least one more child.

From the above discussion, two questions emerge regarding the relationship between gender role attitudes and fertility intentions. First, how do changes in the development of gender behavior relate to the development of gender role attitudes? And second, how does the relationship between factual and attitudinal development relate to fertility (intentions)?

Three steps of changes in gender role attitudes

Concerning the first question, some evidence has been presented that the change in gender role attitudes toward greater equality also follows a stepwise process. The behavioral change in gender roles follows a two-step process that distinguishes between gender equality in the public and private spheres, or that within the family. We anticipate that attitudes toward women’s and men’s roles in the family differ and will follow a three-step process, whereby they will change at different paces, because there are divergent expectations about women’s and men’s behavior. Women are expected to devote their lives to caring for their children, whereas men are expected to be breadwinners. Consequently, attitudinal changes regarding women’s and men’s roles in the family require changes in opposite directions. Because changes in attitudes toward women’s roles in the family are closely linked to changes in attitudes toward their role in the public sphere, we assume these changes will precede those concerning men’s family roles. Moreover, the availability of public childcare services and household assistance from outside the family may delay changes in attitudes toward paternal roles.Footnote 2

As with the behavioral change concerning gender, we assume that attitudinal change starts with the gradual acceptance of women in the public sphere, followed by a change in attitudes toward women’s roles in the family, in particular, by a change in the view that mothers should be the sole carers for children. In a third step, attitudes toward fathers’ roles in the family change: fathers’ as carers of children and practitioners of equal parenting receive greater acceptance.

Attitudinal change may be explained by both exposure and interests. Attitudes may be seen as being formed during childhood in relation to the historical and cultural context of the time. According to this view, gender-role attitudes remain reasonably stable over the life course, shaping subsequent beliefs and preferences (Blunsdon & Reed, 2005; Brewster & Padavic, 2000; Brooks & Bolzendahl, 2004; van Egmond et al., 2010). Gender role attitudes may also be seen as subject to change over the life course, and in particular, at key stages (van Egmond et al., 2010). Using data from the USA, Brooks and Bolzendahl (2004) find support for both arguments. They find that changes in gender attitudes are mainly driven by cohort replacement, but that some changes are due to social structural factors. Bolzendahl and Myers (2004) argue that exposure to new and progressive ideas about gender relations may lead to more favorable attitudes toward gender equality. They see the continued experience of new gender roles in society altering gender attitudes. The participation of women in the public sphere was accepted earlier than gender changes in the family because the increasing proportion of women in education, employment, politics, and other public institutions made it difficult to maintain traditional attitudes of their roles in society. Consequently, throughout Europe, there is a strong consensus that both women and men should contribute to the household income, while there are also strong views that mothers should be the primary caregivers and that children suffer if their mothers work (Testa, 2007). There are also signs of an emerging trend toward the third stage of the gender revolution among younger cohorts, in that many young Europeans believe that family life suffers if men concentrate too much on their work (Testa, 2007).

There are good reasons to believe that women have more interest in promoting gender equality and therefore hold more gender-equal attitudes than do men. Overall, women gain more from equal access to public institutions and from men’s equal participation in care and domestic work. For men, greater gender equality entails more family obligations and more work at home, so they cling to attitudes favoring gender segregation in the private sphere longer than do women.

Gender role attitudes and fertility intentions

The second question concerns the relationship between changes in gender role attitudes and fertility intentions. We may regard people’s decisions about childbearing as responses to the stages of changes in gender roles. In (traditional) gendered societies, where gender attitudes assign clear public and familial roles to women and men, fertility and intentions are high.Footnote 3 During the first stage of the attitudinal changes, when women’s participation in public life becomes widely accepted, but expectations about parental roles remain largely untouched, fertility is expected to fall, and fertility intentions are therefore low (Goldscheider et al., 2015; McDonald, 2000). Such a situation may lead to an unclear and ambiguous situation concerning gender roles (Sjöberg, 2010). For instance, women may feel torn between favoring female employment and career advancement on the one hand and devoting themselves to their children on the other (Sjöberg, 2010). Research has shown that women who perceive a conflict between their roles as a worker and a mother tend to prefer fewer children (Testa, 2007). Likewise, women prefer smaller families in countries where perceptions of such a conflict are stronger. It is argued that women in countries with a wider gap in attitudes toward gender roles may “feel their family tasks as a threat for their working career or they perceive their working career would keep them from being a good mother” (Testa, 2007): 376.

A similar ambivalence may depress fertility intentions during the second and third stages of the change in gender role attitudes when the view that women should bear sole responsibility for family matters erodes, and demands on men to share family responsibilities increase. This may lead to divergent and inconsistent attitudes toward gender roles and to an ambivalent assessment of one’s own or one’s partner’s roles. For example, young men may expect their partner to combine earning with caregiving (and housekeeping), while young women may want a good provider as well as a partner who is an involved father with whom they can share housework (Goldscheider et al., 2010; Testa, 2007). Research indicates that such discrepancies between assigned gender roles are likely to lead to disjunction between attitudes and actual behavior and to dissatisfaction with the situation (Kjeldstad & Lappegård, 2014). Both are found to hamper fertility intentions (Goldscheider et al., 2013; Neyer et al., 2013). Fertility intentions are expected to rise only when the last stage of the gender revolution is reached and support for equality in women’s and men’s roles in the family correspond to greater involvement in family matters by men (for fertility as a whole, see also McDonald, 2000 and Goldscheider et al., 2015).

Gender roles in the public sphere and fertility intentions

Attitudes toward gender roles in the public sphere particularly relate to the expected behavior of men and women in education, the labor market, and political institutions. The relationship between these attitudes toward gender roles and fertility intentions may follow two lines of argument: preferences and gender equality. First, decisions about fertility reflect women’s views about their role in society (Nock, 1987), meaning that preferences for motherhood and work life are reflected in their attitudes toward gender roles in the public sphere. According to Nock (1987), motherhood can be seen as central to traditional women’s lives and identity, while for egalitarian women, it is only one part. In general, we may expect women with egalitarian attitudes to have stronger preferences for work life, and therefore less desire for children. Second, gender equality in the public sphere is mainly about the entry of women through education, labor force participation, and political engagement. This expansion of the women’s realm beyond the home increases their workload as long as all household and care work remains their sole responsibility (Goldscheider et al., 2015). In addition, because no society has reached gender equality in the public sphere, compared with men, women usually need to put more effort into their public engagement to be treated equally. The outcome of this imbalance is pressure on families that reduces the desire for children more for women than for men. One could argue that men’s attitudes toward gender roles in the public sphere do not suppress their fertility intentions as long as women fulfill all domestic duties. However, women’s public participation increases the competition for men and puts demands on them to contribute (more and equally) to family work. From their partners, men may also become aware of the pressure on women to achieve equality in the public sphere and/or to manage the dual burden of work and care. From such arguments, we formulate our first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Women and men with egalitarian attitudes toward gender roles in the public sphere are less likely to have positive fertility intentions than are those with more traditional attitudes.

As long as the gender revolution is incomplete, there is a gap between gender equality in the public and private spheres. As mentioned above, the process of changing gender roles has not followed the same trajectory in all countries, and the process toward more gender equality in the private sphere has not proceeded at the same pace as that in the public sphere. This means that the countries that have progressed further toward public gender equality may face a larger disparity. This leads us to our second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: There is a negative relationship between egalitarian attitudes toward gender roles in the public sphere and fertility intentions that is stronger in countries with larger disparities between public and private gender equality.

Mothers’ role in the family and fertility intentions

In most countries, egalitarian gender roles in the family are still an unfulfilled promise, and this affects women more than men. Kaufman (2000) argues that women who believe in an equal division of housework and childcare may face a different reality compared with women who regard family work as their sole duty. Women with gender-equal attitudes who lack support from their partner and/or regard the division of housework and caring as unequal, unfair, or unjust may reduce their childbearing intention and abstain from further children (Goldscheider et al., 2013; Kaufman, 2000; Neyer et al., 2013). This association has proved to be stronger for mothers than for childless women (Goldscheider et al., 2013; Neyer et al., 2013). We expect men with nontraditional attitudes toward mothers’ family roles to be less inclined than traditionalists to want a(nother) child. This is because those who believe that family work is not women’s sole responsibility perform (or are more under pressure to perform) a larger share of the family chores. However, because it is still women who do the lion’s share of domestic work, the negative association between a belief in domestic equality for mothers and fertility intentions may be stronger among women than among men. Therefore, we have formulated the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: Women and men with egalitarian attitudes toward mothers’ roles in the family are less likely to express positive fertility intentions than are those with more traditional attitudes.

Following the same line of argument as that for attitudes toward gender roles in the public sphere, we assume that the negative association between egalitarian attitudes toward mothers’ domestic roles and fertility intentions is stronger in countries with greater disparities in equality between the public and private spheres. In addition, in countries where the attitudes toward the traditional role of mothers have sufficiently eroded, there might be greater dissonance between women’s and men’s attitudes regarding equality in family work and their behavior. This may create conflicts, which weaken fertility intentions. By contrast, if mothers’ family roles go largely unchallenged and men are unaffected by ongoing changes, we may expect little or no association between men’s attitudes toward mothers’ domestic roles and their fertility intentions. This leads us to our fourth hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4: There is a negative relationship between egalitarian attitudes toward mothers’ roles in the family and fertility intentions that is stronger in countries with greater disparities in gender equality between the public and private spheres.

Fathers’ role in the family and fertility intentions

Attitudes toward fathers’ roles in the family concern the expected behavior of men. In a traditional family with a male breadwinner, the active parenting tasks are carried out by the mother; active fathering may be seen as undermining male identity (Puur et al., 2008), and the gender segregation of public and private work as the “natural” way of completing the family (Kaufman, 2000). As societies move away from the male breadwinner model, fathering becomes more related to expectations about childcare and equal parenting. Modern fatherhood entails more family obligations for men and more investment of time and energy in their offspring (Puur et al., 2008). This may reduce men’s fertility intentions, and in particular, their intentions of having additional children.Footnote 4 For women, on the other hand, holding gender-equal attitudes toward the paternal role means that they want a partner who is an involved father and shares the housework. Because gender-equal active fatherhood remains relatively uncommon, such expectations may curb fertility intentions. In addition, the movement toward gender-equal parenthood has led to a redistribution of parental rights, and in turn, to uncertainty over child custody in cases of parental separation. This uncertainty may reduce fertility intentions. Therefore, we have formulated the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5: Women and men with egalitarian attitudes toward the father’s role in the family are less likely to have positive fertility intentions than are those with more traditional attitudes.

The relationship between attitudes toward fathers’ domestic roles and fertility intentions may be strongly linked to a country’s progress in the gender revolution. Changes in fathers’ roles constitute the last step in the three-step process. Therefore, we expect gender-equal attitudes toward the father’s role in the family to be least prevalent in all countries, and believe that no country has reached a gender egalitarian status with active fatherhood as the norm. We thus expect that across all countries, gender-equal attitudes toward fatherhood are associated with lower fertility intentions. Because the demands on fathers to be active are greater in countries that have moved further toward gender-equal roles, we expect fertility intentions to be lower compared with countries where traditional views of fatherhood have largely remained unchallenged. This leads us to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 6: The negative relationship between attitudes toward the father’s role in the family and fertility intentions is stronger in countries with a greater discrepancy in gender equality between the public and private spheres.

We expect this relationship to hold for both men and women, but to be stronger among men than among women.

Empirical analysis of the relationship between gender attitudes and fertility intentions

Data and methods

We use data from the Generations and Gender Surveys (GGS) (see UNECE/PAU, 2008a; UNECE/PAU, 2008b; Vikat et al., 2007).Footnote 5 We use the first wave of the GGS from Austria, Bulgaria, France, Germany, Hungary, Norway, Romania, and Russia. Our sample comprises nonpregnant women aged 18–42 years and men aged 18–49 years at the time of the interview. We chose these age ranges because the decision to have a child outside these ranges may be influenced less by economic, private, and gender equality considerations than it would at a socially accepted childbearing age.Footnote 6 Moreover, very few of the interviewees outside these age ranges intended to have a(nother) child.

Our investigation focuses on the intention to have a child within the subsequent 3 years (based on the interview date). We concentrate on fertility intentions, but our approach is also applicable to fertility behavior. At the individual level, fertility intentions may be regarded as a suitable predictor of actual behavior (Rindfuss et al., 1988; Schoen et al., 1999; Westoff & Ryder, 1977), provided we specify a time period sufficiently close to the prospective behavior so that we may draw inferences from the respondent’s circumstances and viewpoints at the time of interview to her/his prospective behavior (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1973; Balbo & Mills, 2011; Billari et al., 2009; Quesnel-Vallée & Philip Morgan, 2003; Régnier-Loilier & Vignoli, 2011; Schoen et al., 1999; Thomson, 1997). Given this time period, positive fertility intentions—that is, intentions to have a child within the specified period—prove to be a valid predictor of actual behavior, although they sometimes overestimate actual fertility (e.g., Régnier-Loilier & Vignoli, 2011).

The GGS asks respondents whether they intended to have a(nother) child within the next 3 years. This is a reasonable time frame to assume that the expressed intentions do not simply mirror societal norms about the number of children one should have, but actually reflect the respondent’s reasoned decision. An overview of positive and negative fertility intentions by gender, parity, and country confirms our theoretical expectations and findings from other research: childless women are less inclined to become parents than are childless men. This gender difference persists for parents, but is less pronounced. Women and men in Eastern European countries are more likely to intend to have a first child than are their Western European counterparts. Overall, consistent with the assumption that most people want at least one child, intentions to have a child within the next 3 years are expressed by childless women and men more often than by parents (see Table 5 in Appendix).

We use logistic regressions with intention to have a(nother) child within the next 3 years as the dependent outcome variable.Footnote 7 We estimate two sets of models. First, we look at the influence of the three dimensions of gender role attitudes—gender roles in the public sphere, mothers’ role in the family, and fathers’ role in the family—on women’s and men’s childbearing intentions separately, differentiating between intentions to have a first child and subsequent children. Thus, we recognize that attitudes toward gender-equal roles may change once women and men become parents (Neyer et al., 2013). Second, we estimate the influence of the three dimensions of gender role attitudes on women’s and men’s intention to have a(nother) child, differentiated by country. In this way, we recognize that countries are at different stages of the gender revolution. We could not simultaneously stratify the analysis by gender, country, and parity because the resulting samples were too small.

In the sample, we include respondents who are in a relationship (living apart together, cohabiting, or married) and those who are not in a relationship.Footnote 8 We control for their partnership status, age, educational attainment, and employment status, as well as their partner’s educational attainment and employment status. In the models of parents and the models with all parities, we control for the number of children. In the models with all countries, we control for country of residence and adjust the estimates for intracluster (i.e., country) correlations. Age is coded as either above or below 30 years (up to the specified maximum age for each gender). We followed the International Standard Classification of Education classification to group educational attainment according to three standard levels: basic education, secondary and upper secondary education, and post-secondary and tertiary education. For employment status, we distinguish according to whether the respondents and/or their partners are employed.

Three dimensions of gender ideology

The GGS offers three items that represent each of the gender role attitudes that are the focus of this study. First, attitudes toward gender equality in the public sphere are measured by agreement with the following statement: “On the whole, men make better political leaders than do women.” This is a clear statement about the expected positioning of women and men in the public sphere.

Second, attitudes toward gender equality in the private sphere are divided into those concerning mothers’ and fathers’ roles in the family. Attitudes toward mothers’ roles are measured via the statement: “A preschool child is likely to suffer if his/her mother works.” This item concerns gender assumptions about caregiving in the family as well as about the acceptance of mothers as breadwinners. It also indicates whether women’s participation in the public sphere is accompanied by a shift in gender expectations regarding domestic responsibilities.

Third, attitudes toward the father’s role in the family are measured using the item, “If the parents divorce, it is better for the child to stay with the mother than with the father.” This item addresses fathering, specifically whether the respondent considers a father to be equally well suited as a mother to care for a child. It also addresses men’s rights as fathers and thus the respondent’s acceptance of equal rights in parenting.

For each statement, the respondent could choose ‘strongly agree,’ ‘agree,’ ‘neither agree nor disagree,’ ‘disagree,’ or ‘strongly disagree’. We classified the answers as “traditional gender attitudes” (‘strongly agree’ and ‘agree’), “intermediate” (‘neither agree nor disagree’), and “egalitarian” (‘disagree’ and ‘strongly disagree’).

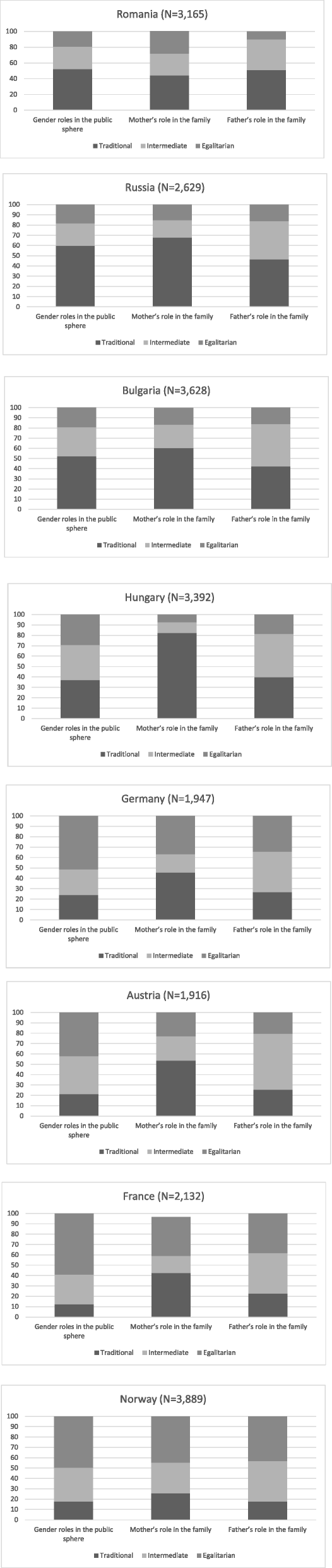

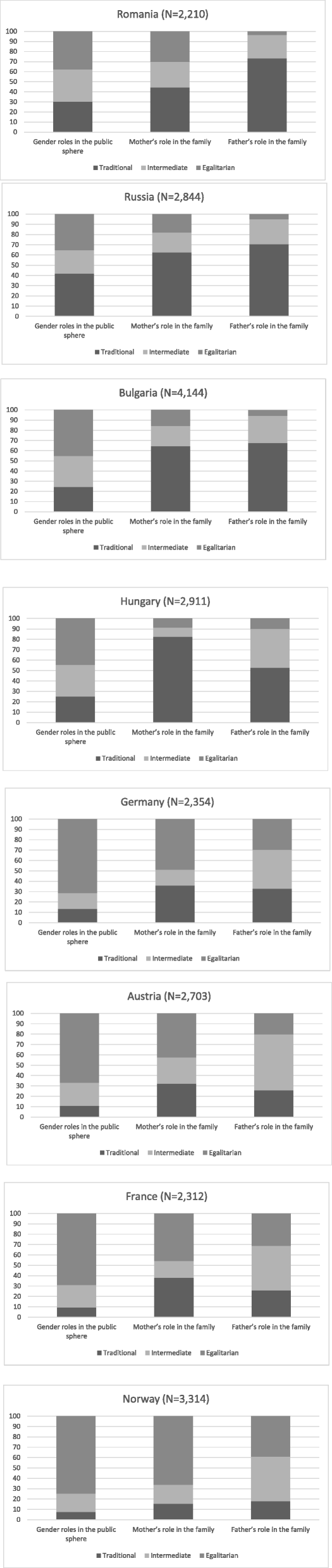

The distribution of attitudes toward the three gender role items varies by country and gender (Figs. 1 and 2). Three issues are especially noteworthy. First, there are generally more egalitarian attitudes toward gender roles in the public than in the private sphere. For instance, 71% of women in Germany have egalitarian attitudes toward gender roles in the public sphere, while 49% have egalitarian attitudes toward a mother’s role in the family. This is not surprising, given that in all countries, the trend toward greater gender equality first affected gender relationships in the public sphere. This generally increased gender equality more in the public than in the private sphere. Second, women are generally more egalitarian than men, except with regard to fathers’ roles. For instance, 45% of women in Bulgaria, but only 19% of men, have egalitarian attitudes toward gender roles in the public sphere. More women express gender-equal attitudes toward mothers’ than toward fathers’ domestic roles. For example, in Austria, 43% of women, but only 20% of fathers, support equality for mothers. By contrast, men’s gender-equal attitudes toward mothers’ and fathers’ roles differ little (except in Romania and Hungary). Third, men and women in Western European countries have more egalitarian attitudes than do those in Eastern European countries. For instance, 59% of men in France hold egalitarian attitudes toward gender roles in the public sphere, whereas only 18% of men in Russia state a similar opinion; likewise, 66% of women in Norway hold egalitarian attitudes toward mothers’ family roles, compared with only 9% of women in Hungary. All these variations support our claim that the relationship between gender role attitudes and fertility intentions needs to be investigated along several dimensions.

Gender ideology by country. Men. Percent. Note: To measure attitudes towards “Mother’s role in the family”, we use the statement: “A pre-school child is likely to suffer if his/her mother works”. The attitudes are classified as either “traditional gender attitudes” (‘strongly agree’ and ‘agree’), “intermediate” (‘neither agree nor disagree’) and “egalitarian” (‘disagree’, and ‘strongly disagree’)

Gender ideology by country. Women. Percent. Note: To measure attitudes towards “Mother’s role in the family”, we use the statement: “A pre-school child is likely to suffer if his/her mother works”. The attitudes are classified as either “traditional gender attitudes” (‘strongly agree’ and ‘agree’), “intermediate” (‘neither agree nor disagree’) and “egalitarian” (‘disagree’, and ‘strongly disagree’)

Results

The estimates of the logistic regression models in which the outcome variable is the intention to have a child within the next 3 years are presented in Tables 1, 2, 3, and 4. Table 1 shows the estimates for all countries pooled, but separated by parity, and Tables 2, 3, and 4 show separate estimates for each country.

We start with the relationship between attitudes toward gender roles in the public sphere, i.e., “On the whole, men make better political leaders than do women” and fertility intentions. For men, there are no statistically significant differences in the relationship between attitudes toward gender roles in the public sphere and fertility intentions, either among childless men or among fathers. For women, there are relevant differences among both childless women and mothers, i.e., women with egalitarian attitudes are less likely than women with traditional attitudes to consider having a child within the next 3 years. The difference between those with egalitarian and traditional attitudes is slightly more pronounced among the childless than among mothers. Overall, this finding confirms the need to investigate the childbearing decisions of women, men, and levels of parity separately (e.g., Neyer et al., 2013), because gender role attitudes play out differently for each. Hypothesis 1 stated that women and men with egalitarian attitudes toward gender roles in the public sphere are less likely than those with more traditional attitudes to want a child within the next few years. This hypothesis holds for women, but not for men. From a theoretical perspective, we argue that egalitarian gender roles in the public sphere have no direct consequences for men, but may operate indirectly through their partners. This means that there are more likely to be differences in fertility intentions among women than among men according to their attitudes toward public gender roles. The estimates from our models support this assumption and suggest that among men, attitudes toward gender roles in the public sphere do not affect their decisions about childbearing.

The models were run separately for each country, and no statistically significant differences among men were found in any country. Hypothesis 2 was that there would be a negative relationship between attitudes toward gender roles in the public sphere and fertility intentions that would be stronger in countries with greater disparities between gender equality in the public and private spheres than elsewhere. This hypothesis cannot be confirmed for men. For women, we find a negative relationship between egalitarian attitudes in Austria and Norway, but not in any of the other counties. Norway is the most advanced country regarding gender-equal attitudes in the public sphere; Austria lags somewhat behind the other Western European countries, but ahead of the Eastern European countries. Hypothesis 2 can thus be partly confirmed for women.

Next, we present the results for the relationship between attitudes toward the mother’s role in the family, i.e., “A pre-school child is likely to suffer if his/her mother works,” and fertility intentions. The results from the model with all countries pooled found no statistically significant association between egalitarian attitudes toward mothers’ family roles and the fertility intentions of childless men. However, a negative relationship was observed between moderate attitudes and fertility intentions among fathers. Turning to women, we find that childless women with moderate and egalitarian attitudes are less likely than women with traditional attitudes to intend to have a child, but we find no such differences among mothers. Hypothesis 3 stated that men and women holding egalitarian attitudes toward mothers’ roles in the family are less likely than men and women with more traditional attitudes to intend to have a child within the next 3 years. This hypothesis is only confirmed for childless women.

The country-specific estimates show both positive and negative relationships between egalitarian attitudes toward mothers’ family role and fertility intentions. Although the results are only statistically precise for some countries, and the significance differs between women and men, they reveal a clear East–West gradient for both women and men. In Eastern European countries, women and men with more gender-equal attitudes toward mothers’ family roles are either more inclined to consider having a child or their childbearing intentions differ little from those who adhere to gender-stereotypical views of a mother’s role (except for women in Hungary). In Western European countries, women and men who express gender-equal attitudes about mothers’ family roles are less inclined than those with traditional attitudes to consider having a child. Hypothesis 4 predicted a negative relationship between attitudes toward mothers’ role in the family and fertility intentions that would be stronger in countries with a greater disparity between gender equality in the public and private spheres. This hypothesis was partly confirmed. We did not expect any positive relationship among either men or women, and the positive relationship between egalitarian attitudes toward mothers’ domestic role and fertility intentions is somewhat surprising. Yet, we find stronger intentions among egalitarian-minded women and men, mainly in the Eastern European countries. Their previous policies of universal childcare and support for mothers may still influence the relationship between attitudes toward mothers’ family roles and fertility intentions.

Last, we present the results from the models of the relationship between attitudes toward the father’s role in the family, i.e., “If the parents divorce, it is better for the child to stay with the mother than with the father” and fertility intentions. Looking at all the countries together, we find no statistically significant differences between men’s attitudes toward the father’s family role and fertility intentions, whereas we find a positive relationship between moderate attitudes and the fertility intentions of mothers among women. In Hypothesis 5, we predicted that women and men with egalitarian attitudes toward fathers’ roles in the family would be less likely than women and men with more traditional attitudes to intend to have a child. This hypothesis could not be confirmed.

The relationship between attitudes toward fathers’ roles and fertility intentions is somewhat different when separate models are estimated for each country. As for the attitudes toward mothers’ roles, we find both positive and negative relationships between egalitarian attitudes toward the father’s family role and fertility intentions. We find a strongly positive relationship for men in Russia and Bulgaria, as well as signs of a positive relationship among egalitarian men in the other Eastern European countries. Because egalitarian attitudes toward fathers’ roles are rare in the Eastern European countries, we assume men with such attitudes belong to a select group (see also previous footnotes). The relationship for men is negative in Austria and Norway, the two Western European countries with the lowest and highest proportions of men with egalitarian attitudes toward fathers’ roles, respectively. Among women, the pattern also shows positive (Hungary and Germany) and negative (Austria) relationships, but with no obvious link to the respective countries’ status of gender equality.Footnote 9Hypothesis 6 predicted that a negative relationship between attitudes toward the father’s role in the family and fertility intentions would be stronger in countries with greater disparities in gender equality between the public and private spheres. This hypothesis can be partly confirmed.

Discussion

The relationship between gender role attitudes and fertility intentions is a complex issue. We analyzed the relationship between gender ideology and fertility intentions in eight European countries using data from the GGS. We considered the possibility that gender role attitudes are influenced by a person’s social and economic status, and included several covariates that are known to be related to people’s fertility intentions. Our main argument in this paper is that gender role attitudes do not constitute a unified entity and cannot be captured by a single measure.

Expanding the theoretical concept of the two-step gender revolution, we suggested that attitudinal changes toward gender equality occur in three steps. The first step concerns gender attitudes toward women in the public sphere, while the second and third concern women’s and men’s roles in the private sphere. In our approach, we assumed that these three attitudinal dimensions affect women and men differently because gender equality influences their lives differently. Furthermore, we argue that countries are at different stages of the gender revolution, so individual gender attitudes depend on the country context. Our empirical results substantiate our theoretical standpoint.

First, our findings support our assumption that the gender revolution in attitudes proceeds in three steps. Gender-equal attitudes related to the public sphere are more widespread than those concerning mothers’ and fathers’ roles in the family. We also find that attitudinal changes proceed at a different pace in different countries. The results of our analyses clearly show that the relationship between gender role attitudes and fertility intentions depends on the area of life that the gender attitude concerns. Attitudes toward gender roles in the public sphere and mothers’ family roles create more variation in fertility intentions than do attitudes toward fathers’ family roles, especially among women. Egalitarian attitudes toward gender roles in the public sphere and mothers’ family roles signal preferences for women combining work and motherhood, which is generally associated with lower fertility. As long as women do the lion’s share of work at home, egalitarian attitudes toward gender equality in these areas create conflicts and are expected to be negatively associated with fertility intentions. The theoretical model predicts that fertility will increase once the father’s role in the family is viewed (and lived) with gender equality. Our results provide some support for this assumption. Although attitudes toward fathers’ family roles create somewhat little variation in fertility intentions among women and men in our sample, we find that mothers with egalitarian attitudes toward fathers’ family roles tend to be more inclined to want another child than are those who adhere to traditional views of the father’s role.

Second, we find that the relationship between gender role attitudes and fertility intentions differs between women and men. In general, gender role attitudes create more variation in women’s than in men’s fertility intentions. The lives of men and women are affected differently by gender equality, which means that the relationship between attitudes toward gender roles and fertility intentions is closer among women than among men. As predicted, egalitarian gender attitudes concerning the public sphere have no effect on men’s fertility intentions, while they reduce both childless women’s and mothers’ childbearing intentions. Attitudes toward mothers’ family roles also have different consequences for women and men. Egalitarian views of a mother’s role restrain the fertility intentions of childless women, but not those of mothers. However, among men, it is egalitarian fathers rather than childless men who tend not to want another child. This indicates that gender ideology influences women’s and men’s fertility decisions differently at different stages of their family life course. Separate models for each country also show variation in fertility intention among men with gender-equal attitudes toward mothers’ and fathers’ role in the private sphere, but no such variation concerning gender roles is seen in the public sphere. In general, men and women have more gender-equal attitudes toward roles in the public sphere than in the family. Gender roles in the public sphere concern women and men in a broader sense, and they do not usually affect their private lives directly. Attitudes toward mothers’ and fathers’ roles in the family concern preferences for different ways of organizing family life, and affect family life and women’s and men’s contributions to family work and care more directly.

Last, we find that the relationship between gender-role attitudes and fertility intentions depends on the gender context in the country. There is extensive variation in gender-role attitudes between countries. Gender-equal attitudes may mean something different in a country where the majority shares the same attitudes than in a country where only a select group has them. We did not find a negative association between egalitarian gender role attitudes and fertility intentions in any of the Eastern European countries, in contrast to Western European countries. However, in the Eastern European countries, we found examples of a positive relationship between egalitarian attitudes toward gender roles in the family and fertility intentions, while no such relationship concerning attitudes toward gender roles was observed in the public sphere. A positive relationship between attitudes toward fathers’ family roles and fertility intentions has been explained by egalitarian fathers being more family-oriented than others and thus placing more priority on family life (Duvander et al., 2010; Duvander & Andersson, 2006; Kaufman, 2000; Miettinen et al., 2011). The same argument, however, cannot be used to explain the positive relationship between attitudes toward mothers’ roles in the family and fertility intentions. Traditional mothers are expected to be more family-oriented than are egalitarian mothers, and a positive relationship may seem puzzling. To get a better understanding of this, we examined whether the relationship was the same among childless respondents and parents. We find (numbers not shown) that the positive relationship in Eastern Europe is dominated by childless people (for Russian men and Romanian women). This positive relationship may reflect the prevalent norm of having at least one child in these countries and may also be influenced by the Eastern European past, with its emphasis on state-supported and work-oriented motherhood. The positive relationship may thus be a temporary status that disappears when the first child is born, and the gender arrangements between partners become more complicated or when childbearing norms are relaxed and the dual pressure on women is not counterbalanced by public childcare support.

Our study provides more nuanced insights into existing research on attitudes toward gender roles and fertility (e.g., Aassve et al., 2015; Arpino et al., 2015; Bernardi et al., 2013; Kan & Hertog, 2017; Miettinen et al., 2015; Okun & Raz-Yurovich, 2019; Oláh et al., 2021; Schober, 2013a, 2013b; Sullivan et al., 2014). However, given the research design that we adopted, the findings remain largely descriptive. Although the theoretical section of this article proposes potential pathways for the association between gender role attitudes and fertility (intentions), the data available did not allow us to investigate all of them in detail. We distinguished between welfare regimes, but we could not study the role of policies as such (e.g., childcare availability). The available literature suggests that the understanding of the mechanisms operating between family policies and fertility dynamics requires a different research setup, such as micro-level (quasi-) natural experiments, as well as reliable, detailed, and comparable policy data (Neyer & Andersson, 2008). Therefore, we deliberately abstain from formulating general or country-specific considerations regarding current or future policies. Nonetheless, this study plants a seed that will—we hope—germinate into future studies on the topic with a broader comparative ambition. To this end, it is crucial to utilize new releases of the GGS that will expand the number of countries available for comparative research compared with the relatively limited set used in this paper.

To conclude, one may contest the implementation of the selected dimensions of gender role attitudes via GGS data. One may also object that a study of this kind requires more countries to reach firm conclusions. As in the vast majority of comparative studies, the lack of statistical significance of one estimate compared with another may simply be due to different sample sizes—so this paper focuses largely on the general narrative and much less on statistical significance (see Bernardi et al., 2017; Hoem, 2008). In addition, one may argue that these dimensions and their representations are interrelated. However, our outcomes provide us with useful input, demonstrating the complexity of the link between gender role attitudes and fertility intentions. They cannot be reconciled with any notion of a simple, uniform, and unidirectional relationship between gender role attitudes and fertility intentions. Instead, they emphasize the need for a multidimensional approach, as outlined in this paper. We question whether it is possible to determine if “gender-equal attitudes” increase or decrease fertility intentions because of the incongruities between attitudes regarding the public sphere as well as mothers’ and fathers’ roles in the private sphere between men and women and between individual and societal levels of gender equality. We further question whether the concept of a two-step gender revolution to describe behavioral changes can be applied to attitudinal changes unconditionally. We have demonstrated that attitudes toward mothers’ and fathers’ family roles do not change simultaneously; support for gender equality in fathers’ family roles lags behind such attitude changes concerning mothers’ roles. From a broader theoretical perspective, this underlines the need to consider which type of gender equality we mean when investigating the relationship between gender equality and social and individual behavior.

The study of the gender aspects of fertility research should not be undermined by recent developments that have seen declines in fertility irrespective of gender equality in countries (Vignoli et al., 2020; Comolli et al. 2021). We believe that our research provides both an empirical and a theoretical contribution to the systematic study of the influence of gender aspects on fertility. That is, we prove that the distinction between gender roles in the public sphere and mothers’ and fathers’ roles in the family is a strategy that discourages oversimplification of the complex gender-related factors in fertility (intentions). Without a clear conceptualization and empirical distinction of the various elements involved in the gender role attitudes/fertility nexus, scientific exercises will continue to send conflicting messages, contributing to a crowded and unclear body of empirical research.

Availability of data and materials

GGS data is available for all researchers.

Notes

Following the Encyclopedia of Sociology, we use gender-role attitudes, gender attitudes, gender ideology, and gender role ideology interchangeably.

This was largely the case in Eastern European countries (Saxenberg, 2014).

This applies, for example, to Western societies of the 1950s and early 1960s, when gender role attitudes and social policies assigned the role of the family provider to men and the roles of homemaker and child-rearer to women.

Some research has shown that families in which the father engages actively in child-rearing have higher child-bearing risks and fertility intentions than do families where the father does not (Dommermuth et al., 2015; Duvander et al., 2010; Duvander & Andersson, 2006; Lappegård, 2010; Neyer et al., 2013). However, this only holds if fathers do some childcare, while equal sharing seems to lower fertility and fertility intentions. It is assumed that fathers who engage in child-rearing are more family- and child-oriented, so they constitute a select group (Duvander et al., 2010; Duvander & Andersson, 2006; Kaufman, 2000; Miettinen et al., 2011).

For more information on the Generations and Gender Programme, see Vikat et al., 2007, UNECE/PAU, 2008a, and UNECE/PAU, 2008b, as well as the homepage of UNECE/PAU (http://www.unece.org/pau/ggp/welcome) and the homepage of the EU GGP Design Studies for Research Infrastructure project (http://www.ggp-i.org).

We chose upper age limits at the approximate midpoint of the socially accepted age ranges found by Billari et al. (2011). Using the European Social Survey for 25 countries, they find considerable variation in socially accepted age limits for fertility in Europe. For men, the accepted upper age limit varies between 45.3 and 51.2 years, and for women, between 39.3 and 43.8 years. We also chose these age ranges to recognize the tendency toward fertility at higher ages, in high-order parities, or the possibilities offered by assisted reproductive technology at higher ages.

Most GGSs offer respondents four response options concerning their intention to have a child within the next 3 years: “definitely yes,” “probably yes,” “probably no,” and “definitely no”. The Norwegian GGS only offers “yes” or “no.” Therefore, we recoded all answers to these two options, collapsing the options “probably” and “definitely.”

This was done mainly to ensure sufficiently large samples for the analyses. There are content-related arguments that support or contest the strategy to pool all relationships. One may argue that the short-term intentions of those who are in a relationship are more “realistic” than the short-term intentions of those who are not. By contrast, one may argue that there is no difference between them, because 3 years is a sufficiently long time frame in which to find a partner (or make use of reproductive technology) to realize one’s childbearing intentions.

If we include the nonsignificant results in our reflections, there is a clear East–West divide. Women in Eastern European countries with gender egalitarian attitudes toward fathers’ family roles tend to be more inclined than those with traditional attitudes to have another child, whereas the opposite applies in Western European countries. This supports Hypothesis 6, that fertility intentions are negative in countries that have moved further along in their acceptance of gender-equal roles for fathers.

References

Aassve, A., Fuochi, G., Mencarini, L., & Mendola, D. (2015). What is your couple type? Gender ideology, housework-sharing, and babies. Demographic Research, 32, 835–858.

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1973). Attitudinal and normative variables as predictors of specific behaviors. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 27(1), 41–57. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0034440.

Arpino, B., Esping-Andersen, G., & Pessin, L. (2015). How do changes in gender role attitudes towards female employment influence fertility? A macro-level analysis. European Sociological Review, 31(3), 370–382. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcv002.

Balbo, N., & Mills, M. (2011). The effect of social capital and social pressure on the intention to have a second or third child in France, Germany, and Bulgaria, 2004–05. Population Studies, 65(3), 335–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324728.2011.579148.

Bernardi, F., Chakhaia, L., & Leopold, L. (2017). ‘Sing me a song with social significance’: The (mis)use of statistical significance testing in European sociological research. European Sociological Review, 33(1), 1–15.

Bernardi, L., Ryser, V.-A., & Le Goff, J.-M. (2013). Gender role-set, family orientations, and women’s fertility intentions in Switzerland. Swiss Journal of Sociology, 39(1), 9–31.

Billari, F. C., Goisis, A., Liefbroer, A. C., Settersten, R. A., Aassve, A., Hagestad, G., & Spéder, Z. (2011). Social age deadlines for the childbearing of women and men. Human Reproduction, 26(3), 616–622. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deq360.

Billari, F. C., Philipov, D., & Testa, M. R. (2009). Attitudes, norms and perceived behavioural control: Explaining fertility intentions in Bulgaria. European Journal of Population, 25(4), 439–465. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-009-9187-9.

Blunsdon, B., & Reed, K. (2005). Changes in attitudes to mothers working: Evidence from Australian surveys. Labour & Industry: A Journal of The Social And Economic Relations of Work, 16(2), 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/10301763.2005.10669321.

Bolzendahl, C. I., & Myers, D. J. (2004). Feminist attitudes and support for gender equality: Opinion change in women and men, 1974–1998. Social Forces, 83(2), 759–789. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2005.0005.

Brewster, K. L., & Padavic, I. (2000). Change in gender-ideology, 1977–1996: The contributions of intracohort change and population turnover. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(2), 477–487. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00477.x.

Brooks, C., & Bolzendahl, C. (2004). The transformation of US gender role attitudes: Cohort replacement, social-structural change, and ideological learning. Social Science Research, 33(1), 106–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0049-089X(03)00041-3.

Ciabattari, T. (2001). Changes in men’s conservative gender ideologies, cohort and period influences. Gender and Society, 15(4), 574–591. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124301015004005.

Comolli, C. L., Neyer, G., Andersson, G., Dommermuth, L., Fallesen, P., Maaarika, J., … Lappegård, T. (2021). Beyond the economic gaze: Childbearing during and after recessions in the Nordic countries. European Journal of Population, 37(2), 1–48.

Davis, N. J., & Robinson, R. V. (1991). Men’s and women’s consciousness of gender inequality, Austria, West Germany, Great Britain, and the United States. American Sociological Review, 56(1), 72–84. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095674.

Dommermuth, L., Hohmann-Marriott, B., & Lappegård, T. (2015). Gender equality in the family and childbearing. Journal of Family Issues, 38(13), 1803–1824.

Duvander, A.-Z., & Andersson, G. (2006). Gender equality and fertility in Sweden: A study on the impact of the father’s uptake of parental leave on continued childbearing. Marriage and Family Review, 39(1–2), 121–142. https://doi.org/10.1300/J002v39n01_07.

Duvander, A.-Z., Lappegård, T., & Andersson, G. (2010). Family policy and fertility: Fathers’ and mothers’ use of parental leave and continued childbearing in Norway and Sweden. Journal of European Social Policy, 20(1), 45–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928709352541.

England, P. (2010). The gender revolution uneven and stalled. Gender & Society, 24, 149–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243210361475.

Evertsson, M. (2014). Gender ideology and the sharing of housework and child care in Sweden. Journal of Family Issues, 35(7), 927–949. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X14522239.

Funk, N., & Müller, M. (Eds.) (1993). Gender politics and post-communism. Reflections from Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. London: Routledge.

Gal, S., & Kligman, G. (2000a). Reproduction as politics. In: S. Gal, & G. Kligman (Eds.), The politics of gender after socialism, (pp. 15–36). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Gal, S., & Kligman, G. (2000b). Reproducing gender. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Goldscheider, F. K., Bernhardt, E., & Brandén, M. (2013). Domestic gender equality and childbearing in Sweden. Demographic Research, 29(40), 1097–1126. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2013.29.40.

Goldscheider, F. K., Bernhardt, E., & Lappegård, T. (2015). The gender revolution: A framework for understanding family and demographic behavior. Population and Development Review, 41(2), 207–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00045.x.

Goldscheider, F. K., Olah, L. S., & Puur, A. (2010). Reconciling studies of men’s gender attitudes and fertility: Response to Westoff and Higgins. Demographic Research, 22, 189–198. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2010.22.8.

Hoem, J. M. (2008). The reporting of statistical significance in scientific journals. Demographic Research, 18(15), 437–442. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2008.18.15.

Inglehart, R., & Norris, P. (2003). Rising tide: Gender equality and cultural change around the world. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511550362.

Jansen, M., & Liefbroer, A. C. (2006). Couples’ attitudes, childbirth, and the division of labor. Journal of Family Issues, 27, 487–1511.

Kan, M.-Y., & Hertog, E. (2017). Domestic division of labour and fertility preference in China, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. Demographic Research, 36(2017), 557–588. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2017.36.18.

Kane, E. W., & Sanchez, L. (1994). Family status and criticism of gender inequality at home and at work. Social Forces, 72(4), 1079–1102. https://doi.org/10.2307/2580293.

Kaufman, G. (2000). Do gender role attitudes matter? Family formation among and dissolution among traditional and egalitarian men and women. Journal of Family Issues, 21(1), 128–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/019251300021001006.

Kjeldstad, R., & Lappegård, T. (2014). How do gender values and household practices cohere? Value-practice configurations in a gender egalitarian context. NORA – Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research, 22(3), 219–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/08038740.2013.864703.

Lappegård, T. (2010). Family policies and fertility in Norway. European Journal of Population, 26(1), 99–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-009-9190-1.

Lesthaeghe, R. (1995). The unfolding story of the second demographic transition. Population and Development Review, 36(2), 211–251.

McDonald, P. (2000). Gender equity, social institutions and the future of fertility. Journal of Population Research, 17(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03029445.

Miettinen, A., Basten, S., & Rotkirch, A. (2011). Gender equality and fertility intentions revisited: Evidence from Finland. Demographic Research, 24(20), 469–496. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2011.24.20.

Miettinen, A., Lainiala, L., & Rotkirch, A. (2015). Women’s housework decreases fertility: Evidence from a longitudinal study among Finnish couples. Acta Sociologica, 58(2), 139–154. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699315572028.

Neyer, G., & Andersson, G. (2008). Consequences of family policies on childbearing behavior: Effects or artifacts? Population and Development Review, 34(4), 699–724. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2008.00246.x.

Neyer, G., Lappegård, T., & Vignoli, D. (2013). Gender equality and fertility: Which equality matters? European Journal of Population, 29(3), 245–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-013-9292-7.

Nock, S. L. (1987). The symbolic meaning of childbearing. Journal of Family Issues, 8(4), 373–393. https://doi.org/10.1177/019251387008004004.

Okun, B. S., & Raz-Yurovich, L. (2019). Housework, gender role attitudes, and couples’ fertility intentions: Reconsidering men’s roles in gender theories of family change. Population and Development Review, 45(1), 169–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/padr.12207.

Oláh, Livia, Daniele Vignoli, and Irena E. Kotowska. 2021. “Gender roles and families.” In: Handbook of labor, human resources and population economics. Springer; pp. 1–28.

Philipov, D. (2008). Family-related gender attitudes: The three dimensions: ‘Gender-role ideology’, ‘Consequences for the family’, and ‘Economic consequences.’. In C. Höhn, D. Avramov, & I. E. Kotowska (Eds.), People, Population Change and Policies: Lessons from the Population Policy Acceptance Study, (pp. 153–174). Dordrecht: Springer.

Puur, A., Oláh, L. S., Tazi-Preve, M. I., & Dorbritz, J. (2008). Men’s childbearing desires and views of the male role in Europe at the dawn of the 21st century. Demographic Research, 19(56), 1883–1912. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2008.19.56.

Quesnel-Vallée, A., & Philip Morgan, S. (2003). Missing the target? Correspondence of fertility intentions and behavior in the U.S. Population Research and Policy Review, 22(5–6), 497–525. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:POPU.0000021074.33415.c1.

Régnier-Loilier, A., & Vignoli, D. (2011). Fertility intentions and obstacles to their realization in France and Italy. Population, 66(2), 361–390. https://doi.org/10.3917/pope.1102.0361.

Rindfuss, R. R., Philip Morgan, S., & Swicegood, G. (1988). First births in America: Changes in timing of parenthood. Berkeley: University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520332508.

Saxenberg, S. (2014). Gendering family policies in post-communist Europe. A historical–institutional analysis. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137319395.

Schober, P. S. (2013a). The parenthood effect on gender inequality: explaining the change in paid and domestic work when British couples become parents. European Sociological Review, 29(1), 74–85. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcr041.

Schober, P. S. (2013b). Gender equality and outsourcing of domestic work, childbearing, and relationship stability among British couples. Journal of Family Issues, 34(1), 25–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X11433691.

Schoen, R., Astone, N. M., Kim, Y. J., Nathanson, C. A., & Fields, J. M. (1999). Do fertility intentions affect fertility behavior? Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61(3), 790–799. https://doi.org/10.2307/353578.

Scott, J. (2008). Changing gender role attitudes. In J. Scott, S. Dex, & H. Joshi (Eds.), Women and Employment: Changing Lives and New Challenges, (pp. 156–178). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781848442931.00014.

Scott, J. W. (1986). Gender: A useful category of historical analysis. American Historical Review, 91(5), 1053–1075. https://doi.org/10.2307/1864376.

Sjöberg, O. (2010). Ambivalent attitudes, contradictory institutions. Ambivalence in gender-role attitudes in comparative perspective. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 5(1), 33–57.

Sullivan, O., Billari, F. C., & Altintas, E. (2014). Fathers’ changing contributions to child care and domestic work in very low-fertility countries: The effect of education. Journal of Family Issues, 35(8), 1048–1065. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X14522241.

Szelewa, D., & Polakowski, M. P. (2008). Who cares? Changing patterns of childcare in Central and Eastern Europe. Journal of European Social Policy, 18(2), 115–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928707087589.

Testa, M. R. (2007). Childbearing preferences and family issues in Europe: Evidence from the Eurobarometer 2006 Survey. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 2007, 357–379. https://doi.org/10.1553/populationyearbook2007s357.

Thomson, E. (1997). Couple childbearing desires, intentions, and births. Demography, 34(3), 343–354. https://doi.org/10.2307/3038288.

Thornton, A., & Young-DeMarco, L. (2001). Four decades of trends in attitudes toward family issues in the United States: The 1960s through the 1990s. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63(4), 1009–1037. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.01009.x.

Torr, B. M., & Short, S. E. (2004). Second births and the second shift: A research note on gender equity and fertility. Population and Development Review, 30(1), 109–130. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2004.00005.x.

UNECE/PAU (2008a). Generations and Gender Programme: Concepts and guidelines. Geneva: United Nations Economic Commission for Europe.

UNECE/PAU (2008b). Generations and Gender Programme: Survey instruments. Geneva: United Nations Economic Commission for Europe.

van Egmond, M., Baxter, J., Buchler, S., & Western, M. (2010). A stalled revolution? Gender role attitudes in Australia, 1986–2005. Journal of Population Research, 27(3), 147–168. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-010-9039-9.

Vignoli, D., Guetto, R., Bazzani, G., Pirani, E., & Minello, A. (2020). A reflection on economic uncertainty and fertility in Europe: The narrative framework. Genus, 76(28), 1–27.

Vikat, A., Spéder, Z., Beets, G., Billari, F., Bühler, C., Desesquelles, A., … Solaz, A. (2007). Generations and Gender Survey (GGS): Towards a better understanding of relationships and processes in the life course. Demographic Research, 17, 389–439. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2007.17.14.

Watkins, S.C. (1993). If all we knew about women was what we read in Demography, what would we know?. Demography, 30, 551–577. https://doi.org/10.2307/2061806.

Westoff, C. F., & Higgins, J. (2009). Relationships between men’s gender attitudes and fertility: Response to Puur et al.’s ‘Men’s childbearing desires and views of the male role in Europe at the dawn of the 21st century. Demographic Research, 19, 1883–1912.

Westoff, C. F., & Ryder, N. B. (1977). The predictive validity of reproductive intentions. Demography, 14(4), 431–453. https://doi.org/10.2307/2060589.

Acknowledgements

Trude Lappegård gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Norwegian Research Council. Gerda Neyer gratefully acknowledges the financial support of Riksbankens Jublieumsfond (Project P20-0517) and of the Swedish Research Council (Project DN 2020-01976) for research on fertility.

Funding

This study was funded by the Norwegian Council of research and The Swedish research council.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The three authors TL, GN, and DV have contributed equally to the paper. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lappegård, T., Neyer, G. & Vignoli, D. Three dimensions of the relationship between gender role attitudes and fertility intentions. Genus 77, 15 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41118-021-00126-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41118-021-00126-6